At EverTrue, we’re on a mission to make the really hard job of fundraising so much easier for every fundraiser – so they can improve the experience of every donor. Because a better donor experience translates into more meetings and more gifts.

We’re delving into the intricacies of donor behavior and cultivation to help organizations find innovative ways to assess their donor pipelines.

Our initial analysis focused on 9,600 major donors who gave $50,000 or more in a year, excluding bequest gifts. These aren’t just faceless organizations; they’re individuals whose generous contributions shape the future. With this data, we aim to provide fresh insights that can transform how organizations build and nurture their major gift pipelines.

Key trends emerged from this study:

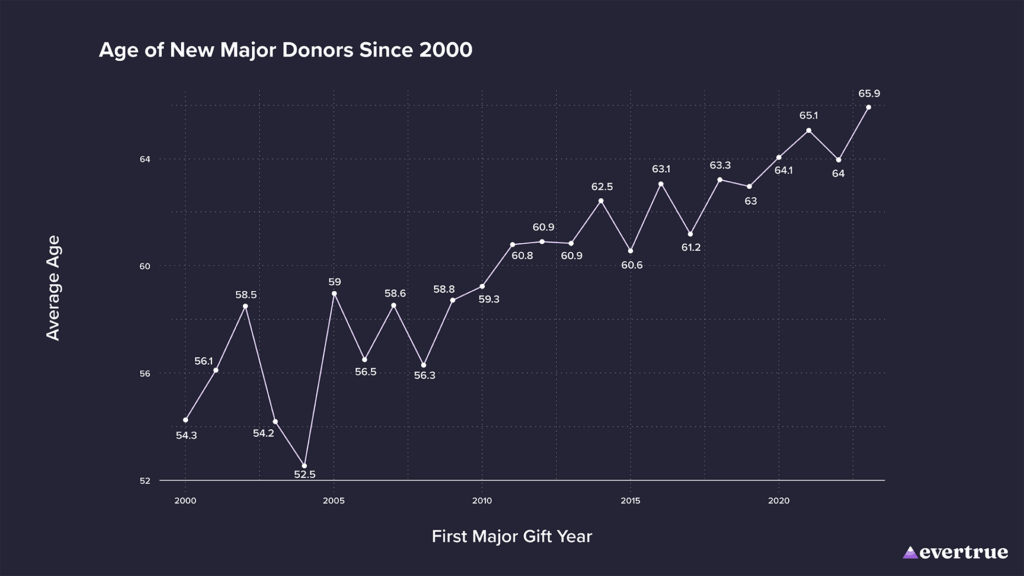

The average age for first-time major donors has risen from 55 to 66 over the last two decades.

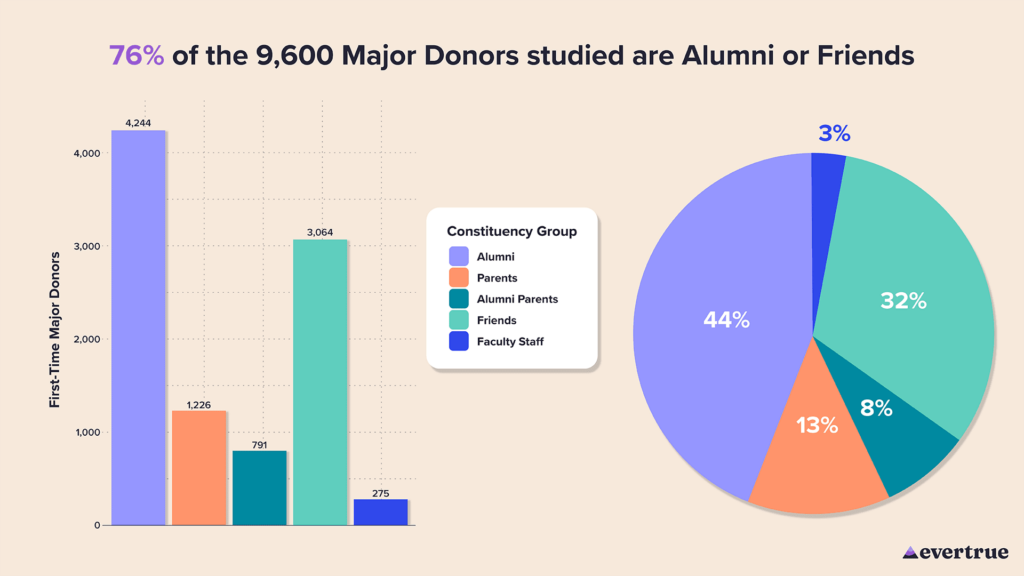

Thirty-two percent of major donors are friends of the institution, signaling potential in expanding donor outreach beyond alumni to include friends and community members engaged with the institution.

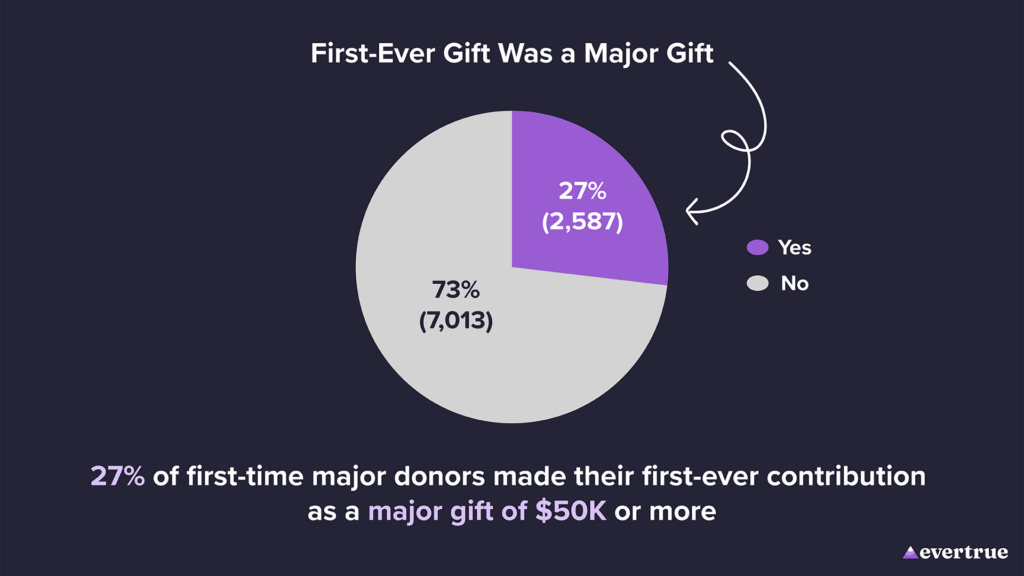

Twenty-seven percent of major donors contribute a significant amount as their first gift to the institution.

A focused view shows that many donors transition to major giving in less than 10 years, with recent trends indicating a shift towards quicker transitions to major giving, suggesting evolving cultivation strategies.

All of these trends point to the need for flexible donor engagement strategies.

- Donor-centric approaches are essential for both rapid and prolonged cultivation periods.

- Success should be measured not just by maturation speed but by the quality and depth of donor engagement.

- Technology and tailored communication play pivotal roles in effective donor cultivation.

Early Trends and Insights into Major Giving:

1. The Age of Major Donors is Increasing

Over the last two decades, the average age at which individuals make their first major donation has increased significantly, from 55 to 66 years. This signals the need for a strategic shift in how institutions approach prospective major gift donors and calls for us to reimagine how we research prospects that feed the major donor pipeline.

This shift toward older first-time major donors could indicate several broader societal and economic trends.

- An aging major gift population might reflect the changing nature of financial stability and wealth accumulation. With the average lifespan growing each year, the window of time we consider to be our “working years” has grown to keep pace. Because of this, individuals may reach financial stability later in life, choosing to make substantial gifts once they have a clearer picture of their long-term financial outlook. This could suggest that the major gift donor population is increasingly shaped by donors who, having spent more years in the workforce, are making more calculated, impactful decisions regarding when to part with their assets.

- Older donors might also be taking their time to understand the issues they care about deeply and the institutions they wish to support, perhaps aiming to ensure that their contributions will have the most meaningful, lasting impact. This likely reflects an increased level of sophistication about philanthropy itself, with potential donors seeking to align their gifts with their values and the causes they find most compelling.

- Fundraising strategies overall are shifting. Today, far more organizations are counting deferred gifts within their campaign totals, a practice that was almost unheard of twenty years ago. Because of this, prospect researchers may increasingly target older prospects, recognizing that these individuals are more likely to have amassed the wealth necessary to make substantial contributions. Older donors have not only the financial means but also a life perspective that drives their philanthropy. This reflects a broader trend of tailoring fundraising efforts to align with demographic realities and potential donors’ capacity to give. By prioritizing older donors, fundraisers might be catalyzing the observed shift in the age of generosity.

In light of this, development officers might consider implementing more personalized, value-driven engagement strategies that resonate with older donors’ desire to make a meaningful difference. This could involve deeper conversations about the institution’s vision and the societal impacts of their potential contributions, as well as more flexible, creative giving options that reflect the unique financial planning and philanthropic vehicles of the demographic.

All of this emphasizes the need for institutions to invest in sustained, meaningful engagement efforts that keep potential donors connected and informed, gradually building towards the possibility of a major gift.

2. Constituencies Engage Differently

The diversity in institutional relationships among our major donor community, with 44% alumni and 32% friends of the institution leading the way, illustrates the multitude of connections individuals have with higher education institutions and the variety of motivations that drive their generosity.

Understanding these diverse relationships is crucial because it underscores the need for personalized engagement strategies that resonate with each unique donor segment.

- Alumni (44%) may be motivated by a sense of loyalty and gratitude for their formative years, aiming to give back to the community that played a pivotal role in their personal and professional development. Their connection to the institution is rooted in personal experience, often making their approach to giving one that seeks to enhance student experiences or academic excellence.

- Friends of the institution (32%) may not have a direct personal history with the institution but are drawn to its mission, impact, or the specific initiatives it champions. Their motivation can stem from a belief in the value of education itself, in the impact its research has on the world, or in the specific causes that the institution supports. For these donors, engagement strategies that highlight the institution’s role in addressing societal challenges or advancing knowledge in areas of interest can be particularly compelling.

This nuanced understanding of donor constituencies is essential. It supports the development of engagement and solicitation strategies that speak directly to the specific values and motivations of each group. Tailoring communication and engagement efforts not only respect the unique relationship each donor type has with the institution but also enhances the likelihood of continued and increased support.

The substantial representation of friends in the donor base challenges conventional wisdom about who the most likely major donors are, suggesting that institutions could benefit significantly from:

- Expanding their focus beyond their alumni network. This could entail identifying potential donors among those who have attended events, engaged with the institution through community programs, or indicated their interest through social media.

- Broadening the narrative around the impact of giving, ensuring that it encompasses the totality of what an institution contributes to society. By doing so, institutions can appeal to a broader spectrum of potential donors by connecting with their varied interests and motivations.

3. Not All Major Donors Start Small

The finding that 27% of major donors gave a large amount as their first gift challenges traditional ideas about donor cultivation. Instead of assuming all major donors start with smaller gifts, this suggests we shouldn’t overlook non-donors as potential major donors.

This also raises questions about the motivations and circumstances leading these individuals, particularly ‘friends’ of the institution, to make such substantial contributions right out of the gate. Notably, these ‘Friends’ account for 65% of major donors giving $50,000 or more as their first gift, surpassing their 32% representation in the sample.

Expanding Prospecting Beyond Alumni

‘Friends’ of institutions make significant first-time gifts, suggesting we should look beyond just alumni. Using data analytics and social listening tools can help find potential donors who, while not alumni, strongly support the institution’s mission. Personalized outreach highlighting their interests and the impact of their support can be very effective.

Understanding Donor Engagement

Analyzing fundraisers’ interactions and reports before these major first-time gifts can show how donors were engaged before giving. Identifying what resonated with these donors can help refine fundraising strategies and better understand the donor journey, especially for those making major gifts as their first contribution.

What could be driving this?

- Targeted capital campaigns and projects that align with donors’ values and interests are becoming more visible and impactful. These initiatives, widely publicized across various media, can quickly attract substantial support from those who see a strong connection between their personal philanthropic goals and the institution’s objectives.

- The evolving wealth creation and philanthropy landscape is another driver. A financially established segment of society is accumulating wealth more quickly and showing more willingness to engage in philanthropy later in life.

- The digital age also plays a role by providing easy access to information, allowing potential donors to connect with causes they care about without prior engagement.

4. Major Gift Cultivation Timelines Vary Widely

Our analysis shows a varied major gift cultivation timeline, with a median of 10 years and an average of 14 years. This reveals changes in how donor relationships form over time, challenging traditional methods and suggesting new, innovative approaches.

By understanding these trends, we can adapt our engagement strategies to meet the changing needs of potential major donors, encouraging faster and more meaningful contributions and creating new opportunities for building relationships.

This data not only shows a consistent distribution but also highlights many donors who become major givers in under 10 years, especially those engaged for less than 5 years.

Here’s a Detailed Breakdown by Cultivation Period:

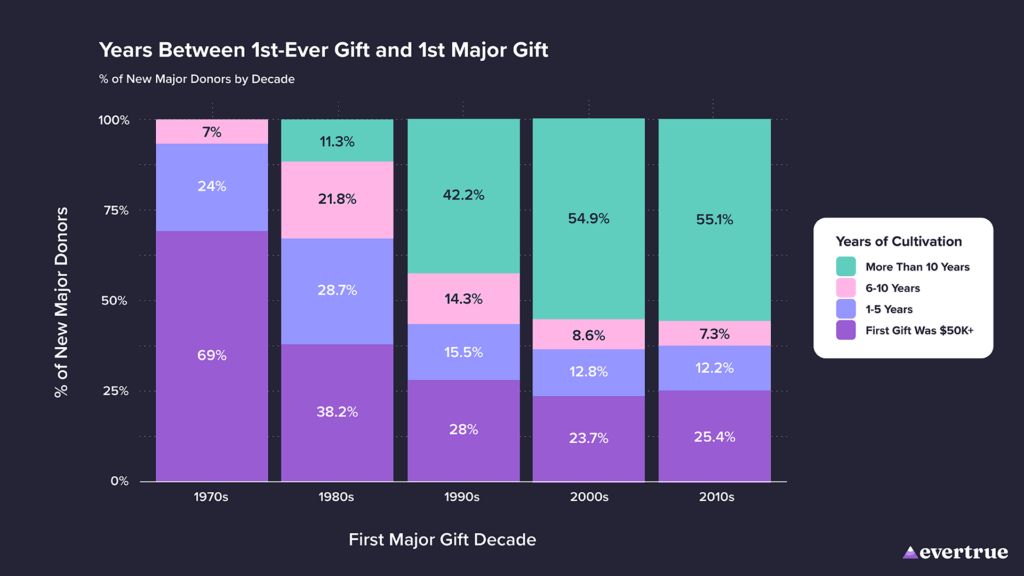

We segmented the donor population based on their specific cultivation timelines into four distinct groups. This segmentation, illustrated over the decades, has revealed two pivotal trends:

A substantial increase in donors requiring over 10 years of cultivation before their first major gift has occurred—from 11% in the 1980s to 55% in the 2000s and 2010s. This pattern has remained stable since 2000, indicating a need to rethink and streamline our cultivation approaches for more effective, efficient, and quicker engagement.

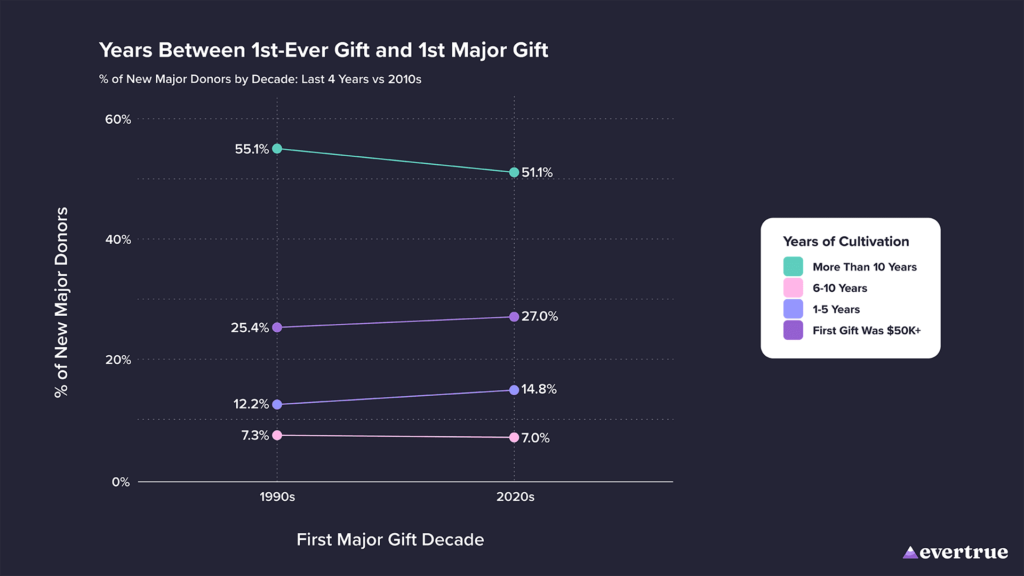

From 2020 to 2023, major gift cultivation timelines have shifted significantly. There’s been a 4% decrease in donors taking more than 10 years to contribute, with more donors now making major gifts within five years. This change suggests a realignment of strategies, potentially influenced by Donor Experience Officers identifying donors ready to give sooner and broadening engagement efforts.

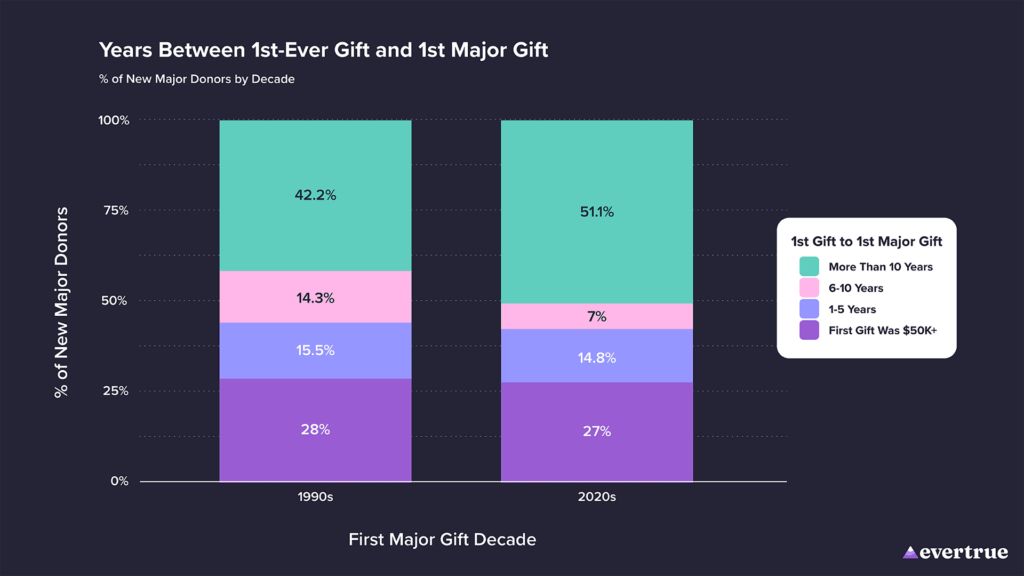

A Comparative Perspective – Back to the 90s!

Looking back over the last four years compared to past decades, today’s trends echo the 1990s, but with fewer donors taking 6 to 10 years to make their first major gift. This indicates a move toward either very quick or much longer donor cultivation periods.

This reduction underscores a significant shift in mid-range cultivation timelines, possibly indicating a more polarized approach where donors are either quickly motivated to make substantial gifts or require more than a decade of nurturing.

This split suggests we need to rethink how we approach donor engagement and cultivation. For donors ready to give quickly, using technology and data can help us match opportunities to their immediate interests. For those who take longer, building strong, ongoing relationships is key, focusing on regular updates and showing the real impact of earlier, smaller gifts.

This split suggests we need to rethink how we approach donor engagement and cultivation and highlights the need for a flexible, donor-centric approach to fundraising strategies.

- For rapid engagers, institutions might leverage technology and data analytics to provide timely, relevant, and compelling opportunities that resonate with these donors’ immediate interests and willingness to impact.

- For those requiring longer cultivation, a focus on relationship building, regular communication, and engagement opportunities that demonstrate the tangible outcomes of smaller contributions over time could be more effective.

- The data also suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach may be less effective than a tailored, scalable strategy that considers the individual donor’s journey, motivations, and readiness to contribute at higher levels.

Looking Forward

Our research is driven by a shared commitment to advancing the mission of higher education and fundraising institutions through strategic, insightful philanthropy and thoughtful technology that supports the next generation of fundraisers.

As we forge ahead in search of new insights, we invite you to join us in pondering some critical questions:

- How do the trends we’ve uncovered resonate with your institution’s experiences?

- What innovative strategies can we develop together to expedite the donor cultivation process, making major giving more accessible and appealing to a broader spectrum of donors?

- How might the role of donor experience officers evolve to address the shifting landscape of donor engagement and cultivation?

As we continue to explore and expand our research, we look forward to sharing valuable insights that help you transform major giving. Let’s collaborate to advance the mission of your institutions and create impactful donor experiences. Together, we can drive the future of fundraising in higher education.