Article originally published in the November 2016 issue of CASE Currents and written by Toni Coleman

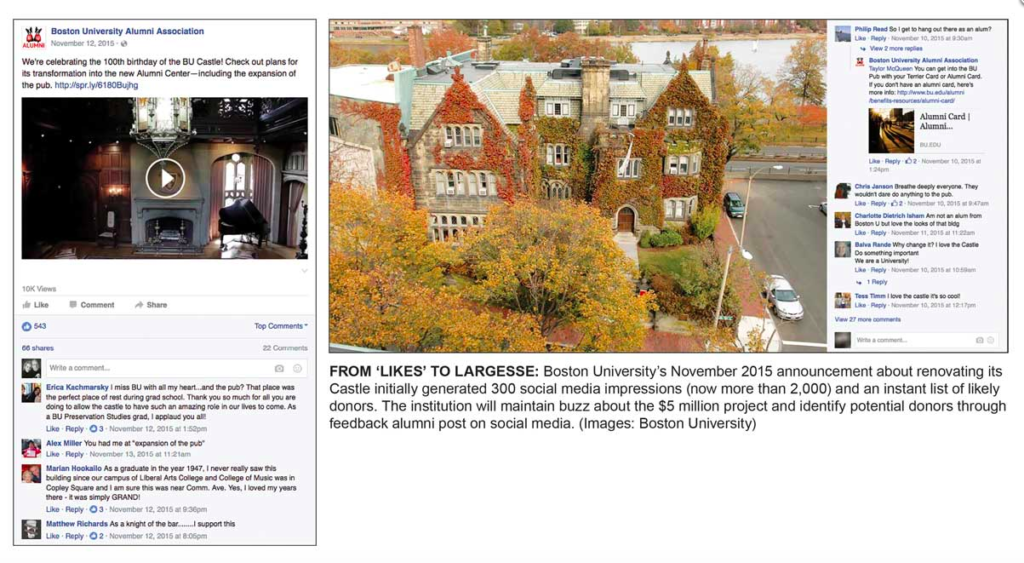

In fall 2015, Boston University shared big news on its website and Facebook pages about its 100-year-old Castle. The building—formerly the president’s home and now a venue for weddings and special events—would be converted into an alumni center. The posts generated more than 300 likes, shares, and comments.

Armed with that list of engaged and interested people, telefund callers went to work. “Did you know that we’re building an alumni center at the Castle? Would you like to support the renovations with a gift of X amount?”

The average conversion rate for phone solicitations—the percentage of people who pick up and give—is 30 percent. For this group, it was 75 percent, says Stephanie Quinn, BU’s director of annual giving.

With a couple of simple posts—and the ability to capture alumni reactions—BU quickly whittled down its prospective donor pool of 320,000 alumni to a few hundred people more likely to support the $5 million Castle renovation.

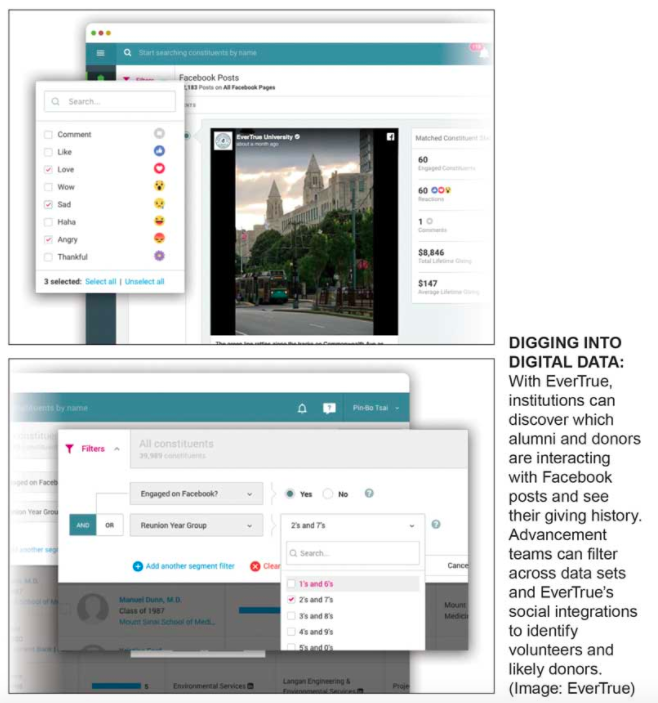

“This group has an interest in this particular topic. They have self-selected,” Quinn says. She credits EverTrue, the platform BU uses to connect social media interaction with its alumni/donor database, for the successful targeting. “It allows us to segment based on interest, rather than on our standard ‘What school did you go to? What year did you graduate?’ It gets us closer to what alumni are most likely to donate to.”

Schools and universities are harvesting information alumni self-report or using behavioral analytics—how people react to content—to drive communications, engagement, and fundraising strategies. Social media insights allow institutions to identify prospects and volunteers and better understand existing ones.

BU’s experiment provides a template for the Castle and other campaigns: Build buzz with content, such as a live-streamed walk through of the Castle’s renovations, and mine the interaction for obviously interested, potential donors.

“If you can push volunteer opportunities, solicitations, and engagement opportunities to people on the basis of their recent interaction with content on Facebook, you know they’re interested because you have evidence,” says Andrew Gossen, senior director of digital innovation at Cornell University in New York. “That’s a data-driven way to decide who you’re going to target.”

It seems like a simple idea. Reach out to alumni based on the interests they share on sites like Facebook and LinkedIn. Until the development of recent technology allowing the interface between social media pages and institutional alumni databases, colleges and universities found it difficult to capture that information. Institutions already collect a lot of data that’s difficult and time-consuming to sort and analyze, and despite best efforts to monitor alumni’s lives, much of the information is old and incorrect.

“We’re in a glut of information, but we’re paralyzed because we don’t have the tools to analyze it,” says Scott VanDeusen, director of development at St. John’s University in New York. “That’s one of the things companies are looking to help us with. How do we take the inordinate amount of information we have and use it to make decisions and create appropriate and meaningful communications?”

CEO Brent Grinna developed EverTrue after a baffling experience as the volunteer leader of a fifth-year reunion campaign at his alma mater. Grinna received a spreadsheet with classmates’ phone numbers, but most of them were out-of-date. He instead connected with fellow alumni via social media and mobile numbers he’d collected. “There was more information outside the donor database than in it,” he says.

Many of the metrics used to gauge alumni affinity and engagement are outdated because institutions aren’t tracking constituent attitudes online, Grinna says. Alumni who “like” content institutions post on social media may not “give, volunteer, or go to a reunion. But they’re highly engaged in social media, which means they’ve been undercounted.”

Much of the innovation is coming from companies with proprietary software, such as EverTrue, Cerkl, IBM, and QuadWrangle, as many colleges and universities lack the bandwidth to constantly monitor social media. But monitor they must. One recent survey found that 72 percent of people who complain to a company via Twitter expect a reply—within the hour.

Oregon State University Foundation uses EverTrue to, among other things, prioritize responses. The program is synced to OSU’s database, so if a high-capacity prospect comments on a post, the foundation can alert the assigned gift officer.

“Years ago, we had an alum in the South, a principal gift prospect. Someone heard that this person didn’t like athletics. We sent a gift officer. What did they talk about? They talked about athletics. If we had this product back then, we would have known this person commented 243 times on how athletics builds leadership,” says Mark Koenig, OSU Foundation’s assistant vice president for advancement services. “They’re engaging with us online. They’re talking to us. Two years ago, we weren’t responding to them. There wasn’t a lot of interaction going on.”

The new tools led to a change in how OSU views engagement. The foundation tested a theory: that engaging heavily on Facebook was akin to attending an event. Researchers identified about 100 constituents who were active on OSU’s Facebook page but did not give, attend events, or volunteer. Each was assigned a development officer.

Typically, about 25 percent of prospects will reply to gift officers’ cultivation overtures, Koenig says. “In this case, we had a 44 percent return.” Today, if you comment more than five times on posts in a year, or like 25 Facebook posts in a year, you’re considered engaged.

At Michigan State University, social media interaction is now used, along with giving history and event attendance, as a metric for engagement; of 177 touch points, five relate to social media engagement, says Monique Dozier, assistant vice president of advancement information systems and donor strategy.

MSU uses IBM software to analyze social media text. The goal: to mine constituents’ impressions of the institution. If MSU has an alumnus’s token, or social media handle, they can match comments directly to the alumnus’s database record.

Analyzing unstructured data helps MSU to determine outreach strategy. During the Big 10 football championship in December 2015, MSU analyzed social media chatter pre- and post-event. “Who was there? Were prospects there? What were their sentiments? It’s not just about fundraising—it’s about profiling your audience,” Dozier says.

MSU discovered that a number of high-capacity nondonors were at the game—and enjoying it. In fall 2016, perhaps at homecoming, MSU plans to host a more intimate event to cultivate these engaged nondonors. “During homecoming, we have tens of thousands of visitors on campus,” Dozier explains. “It’s impossible to connect with everyone. We can target these people to meet us versus us trying to find them.”

Such insight into alumni attitudes and interests helps with targeted appeals, which typically generate on average a 60 to 75 percent response rate for MSU. “A student wants to raise money for an initiative,” Dozier says. “We’re not going to spread the word to a half-million folks. We’ll look for keywords in both responses to posts and in call reports of gift officers.”

Using sentiment analysis to develop a prospect list “is not a one-off thing for us anymore,” Dozier says, noting that MSU uses the same technology to target alumni for specific events.

Some software obtains insights on alumni interests based on behavior. If you consistently read stories in your alma mater’s newsletter about medical research but never open sports news, for instance, platforms know that and adjust content directed at you accordingly. That’s how the platform Cerkl works. Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna University and Ohio’s Xavier University are among institutions that use Cerkl to target communications and asks.

“The important thing is understanding what our alumni want to see and giving them the opportunity to say, ‘This is what interests me.’ That’s dialogue. If it’s only what we decide, it’s monologue. We get further in building relationships when we’re in two-way relationships,” says Ron Cohen, vice president of university relations at Susquehanna.

“We now generate more content in one day than we did from the beginning of time to 2003,” says Tarek Kamil, CEO and founder of Cerkl. “It’s no wonder colleges and universities are having a hard time engaging students and alumni. People tune you out unless you provide real value and relevant content.”

Cerkl institutions send alumni and other constituents an introductory email to join the platform. Once signed in, participants choose their top five of 20 interest areas, the frequency and day/time they’d like to receive the newsletter, and in what format (headlines only or headlines and photos). The system monitors which stories from the newsletter a person reads and adjusts future selections of stories to fit a user’s interests. “Based on your behavior, say, if you stop reading sports, we know to stop sending you that information. It’s all done automatically,” Kamil says.

“The lead story is the most engaging thing we can find for you. Everything else is what’s most popular among other readers,” Kamil says. At Xavier, he says, the open rates for the emailed computer-generated newsletters increased 168 percent, and click-thru rates jumped 207 percent. The unsubscribe rate decreased 98 percent.

With solid data on alumni interests, institutions can also refine their editorial calendars, identify likely attendees for specific events, and boost fundraising efficiency and totals.

At Xavier, which uses Cerkl to pinpoint donor interests, first-time gifts increased, as did the frequency and size of gifts from recurring donors, says Jack Kelley, the former director of corporate philanthropy.

“In the past, your efforts relied on mass communications to reach prospects and donors. It was always a hit-or-miss proposition,” Kelley says. “Instead of a shotgun approach, we targeted those individuals. Because we knew their sweet spot, our results were that much greater. Instead of me cold-calling you and we have two or three lunches, technology cuts the timeline for cultivation to a fraction. We get to know each other faster.”

Improved efficiency is a selling point CEO Nick Zeckets uses to promote QuadWrangle, which leverages machine learning to analyze information alumni self-report on social media. Alumni opt in to the platform and connect their social profiles.

Most donors will never know about two or three giving opportunities perfectly suited for them, says Zeckets, a co-founder of QuadWrangle. “We can make those connections,” he says. “When you look at a donor, we tell you here are the funds he or she is most likely to donate to.”

Zeckets recounts learning about a fundraising appeal for a new pool at the high school he attended—after the campaign. He was once a record-setting member of the swim team and should have been targeted as a prospect. “I thought that was an absolute travesty that I hadn’t been asked to give,” Zeckets says. “I was the rule rather than the exception, given alumni participation rates.”

“It’s not only the speed of discovery, it’s also about alignment between gift officer and donors,” Zeckets says of the tool’s benefits. “If I have a donor who’s clearly expressing interest in women’s STEM initiatives, it makes more sense for a major gift officer in engineering to make that call. She’s going to get routed there anyway, if anyone figures out that’s what she’s interested in.”

QuadWrangle’s platform interprets online behavior, social data, and the data in an insitution’s database to automate a personalized experience for alumni and donors. “As you’re reading stories online, we know what you’re doing, and we continue to feed you more of what you’re interested in,” says St. John’s VanDeusen, who uses QuadWrangle.

Without knowing current interests, VanDeusen says, institutions are pigeonholing donors based on past activities. Say a $50 annual donor to the business school is a fan of fine arts, evidenced by the amount of arts-related university news he consumes. “By logging in to the app, I know you’re interested in the fine arts. You’ll get calls about the cool thing happening in the fine arts department. It changes the conversation.”

VanDeusen likes that the system can quickly generate a prospect list based on proven interests, although St. John’s hasn’t yet used the tool for fundraising. He’ll put that to the test this academic year with a call to action to support the Catholic Scholars Program.

“My biggest competitors aren’t in higher education,” VanDeusen says. “My competitors are Catholic Ministries, Catholic Charities, Greenpeace. We need to figure out in higher ed: How do we compete with that? We need to know alumni interests now, not their interests when they graduated. Millennials aren’t loyal to institutions—they’re loyal to causes. If I can put something in front of them that matches their personal beliefs, they’ll give.”

How do alumni feel being about monitored? They may not know.

“There’s a fine line with this work where you don’t want to say, ‘We noticed you liked the Castle on Facebook.’ That gets a little creepy,” says Quinn of BU, adding that the tools are meant to help institutions identify a potential area of interest among alumni.

Targeting alumni based on their online behavior is reminiscent of remarketing, when people who’ve browsed products online will see ads for those products when they visit other websites. Remarketing is one reason internet privacy efforts are gaining steam: 93 percent of U.S. adults say that it’s important to control who accesses information about them, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey.

But Kelley notes a distinction between Cerkl and Google ads: “We’ve already told them we’ll be sending emails and have asked them to tell us what they want. They know they’ve self-identified prior to our knocking on the door.”

VanDeusen of St. John’s says the information gathering is so subtle alumni may not even notice. Referring back to the business school donor who likes fine arts, VanDeusen adds, “A fine arts story just happens to be one of many stories.”

Alumni, Cohen says, expect their alma mater to know them. Susquehanna’s 19,000 graduates “had a very personal four-year undergrad experience. They hold us to a standard of familiarity that’s reasonable.” The benefits gained from the information gathering outweigh potential downsides, he says. “There’s an opportunity for people to feel better about the place that they attended because they feel like the place they attended knows them.”

Cornell’s Gossen says the tools do not violate people’s privacy. “It’s no different than inviting people to an event, tracking who shows up, and associating that with their record. It’s all happening in public,” he says.

Before using EverTrue, Cornell manually compared the names behind 300 social media interactions to those in its database. It took one person eight hours. The time-saving technology, Gossen says, allows you to think about who these people are and what you can learn from their interest in your content.

Gossen says these technologies represent a leap forward for alumni relations, communications, and development shops. “With tools like this, we can see what people are interested in right now and produce a better user experience for alumni. It keeps us from spamming everyone with the same message. They’re given things that are relevant to their interests.”

Not everyone is sold. Peter Fader, the Frances and Pei-Yuan Chia Professor of Marketing at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, says institutions would be better off fully leveraging the donor data they already collect and use old-school recency, frequency, and monetary analyses to better predict giving behaviors.

Social insight “is not as needle-moving as institutions might think,” he says. “When it comes to behavior, I’m interested in what people are doing as opposed to what they’re saying. Social sharing is more saying than doing. It’s in a different medium, but it’s still talk. I want companies and nonprofits to exhaust [proven methods] before they do the cool new stuff.”

Original content that celebrates innovative thinking in fundraising.

Privacy Policy | © 2023 Evertrue LLC